Introduction

Welcome to Learning copper-rs, a hands-on guide to building robots with the Copper deterministic robotics operating system.

Most people learn Rust with the amazing Rust Book, so we built it for copper-rs.

This book has been written with the help of AI, for the sake of speed, proper grammar and formatting, but each and every line has been reviewed by a human.

The source for this book is available on GitHub. Feedback and contributions are welcome.

This book will take you from zero to a running Copper project, one concept at a time. By the end, you’ll understand how to define task graphs, write sensor drivers and processing pipelines, and run everything with sub-microsecond deterministic scheduling.

Who is this for?

This book is aimed at:

- Robotics developers coming from ROS / ROS 2 who want to explore a Rust-native alternative

- Rust developers interested in robotics and real-time systems

- Beginners who want a gentle, progressive introduction to Copper’s architecture

No prior Copper experience is required. Familiarity with Rust syntax is helpful but any experience with other programming language should allow you to get through.

Let’s get started!

What is copper-rs?

Copper is a deterministic robotics runtime written in Rust. Think of it as a “game engine for robots”: describe your system declaratively and Copper will create a custom scheduler and run it deterministically from cloud simulation down to embedded controllers.

The big idea

You describe your robot as a task graph – a directed graph of components that produce, process, and consume data. Copper reads this graph at compile time and generates a custom deterministic scheduler. At runtime, your tasks execute in a precise, pre-computed order with zero overhead.

┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ Sensor │────▶│ Algorithm│────▶│ Actuator │

│ (Source)│ │ (Task) │ │ (Sink) │

└──────────┘ └──────────┘ └──────────┘

Key features

- Rust-first – Ergonomic and safe.

- Sub-microsecond latency – Zero-alloc, data-oriented runtime.

- Deterministic replay – Every run, bit-for-bit identical.

- Interoperable with ROS 2 – Bridges via Zenoh, opening the path for a progressive migration.

- Runs anywhere – From Linux servers, workstations, and SBCs to bare-metal MPUs.

- Built to ship – One stack from simulation to production.

How it works (in 30 seconds)

- You define your tasks (Rust structs that implement a trait).

- You wire them together in a configuration file (

copperconfig.ron). - A compile-time macro reads the config and generates the scheduler.

- At runtime, Copper calls your tasks’

process()methods in the optimal order, passing pre-allocated messages between them.

That’s it. No topic discovery, no callback registration, no middleware configuration. Define, wire, run.

copper-rs vs ROS

If you’re coming from ROS or ROS 2, this chapter maps the concepts you already know to their Copper equivalents. The mental model is similar. Both are component-based frameworks with message passing, but the execution model is fundamentally different.

Concept mapping

| ROS 2 | copper-rs | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Node | Task | A unit of computation |

| Publisher | CuSrcTask | Produces data (sensor driver) |

| Subscriber + Publisher | CuTask | Processes data (algorithm) |

| Subscriber | CuSinkTask | Consumes data (actuator) |

.msg file | Rust struct with derives | Message definition |

| Topic | Connection in copperconfig.ron | Data channel between tasks |

| Launch file + YAML params | copperconfig.ron | Graph topology + task parameters |

colcon build | cargo build | Build system |

package.xml / CMakeLists.txt | Cargo.toml | Dependency management |

| Executor | #[copper_runtime] macro | Generated deterministic scheduler |

rosbag | Unified Logger + cu29-export | Record and replay |

| Parameter server | ComponentConfig in RON | Per-task key-value configuration |

Key differences

Scheduling

In ROS 2, nodes are separate processes (or threads in a composed executor). Callbacks fire asynchronously when messages arrive via DDS. The execution order depends on network timing and OS scheduling – it’s non-deterministic.

In Copper, tasks run in the same process and are called synchronously in a compile-time-determined order. Every cycle, every task runs in the exact same sequence. There are no callbacks, no races, no surprises.

Message passing

In ROS 2, messages are serialized, sent over DDS (a network middleware), deserialized, and delivered to callbacks. This adds latency and allocations.

In Copper, messages are pre-allocated buffers in shared memory. A task writes its output directly into a buffer that the next task reads from. No serialization, no copies, no allocations on the hot path.

Replay

In ROS 2, rosbag records and replays topic messages. Replay is approximate – timing

jitter, OS scheduling, and node startup order can cause differences.

In Copper, replay is deterministic. The unified logger records every message and periodic state snapshots (“keyframes”). Given the same log, replay produces identical results every time, down to the bit.

Configuration

In ROS 2, you typically write a launch file (Python or XML), separate YAML parameter files, and topic remappings. These are resolved at runtime.

In Copper, everything is in one RON file (copperconfig.ron) that is read at

compile time. If your config references a task type that doesn’t exist, you get a

compile error, not a runtime crash.

Bridges

The good news is that you do not have to chose between Copper and ROS: Copper’s Zenoh bridge lets you run both side by side, so you can migrate incrementally.

Setting Up Your Environment

Before we can build a Copper project, we need Rust and the Copper project template.

Install Rust

Follow the official installation guide at https://rust-lang.org/tools/install/, or run:

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

After installation, make sure cargo is available:

cargo --version

Install cargo-generate

cargo-generate lets you scaffold a new Copper project from the official template:

cargo install cargo-generate

Generate our first simple Copper project

Clone the copper-rs repository and use the built-in template tool:

git clone https://github.com/copper-project/copper-rs

cd copper-rs/templates

cargo +stable generate \

--path cu_project \

--name my_project \

--destination . \

--define copper_source=local \

--define copper_root_path=../..

This generates a complete, ready-to-compile Copper project at the path you specify.

For more details, see the official documentation: https://copper-project.github.io/copper-rs/Project-Templates/

What you get

The generated project contains everything you need:

my_project/

├── build.rs # Build script (required by Copper logging)

├── Cargo.toml # Dependencies

├── copperconfig.ron # Task graph definition

└── src/

├── main.rs # Runtime entry point

└── tasks.rs # Your task implementations

In the next chapter, we’ll explore what each of these files does.

Try it

You can try to compile and run your project:

cd my_project

cargo run

It will compile and run, and you’ll start to receive some messages:

00:00:01.1781 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:01.1781 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

Kill the process and let’s move to the next chapter.

Project Structure Overview

Let’s look at what’s inside a Copper project and understand the role of each file. Here’s the layout generated by the template:

my_project/

├── build.rs # Build script (sets up logging index)

├── Cargo.toml # Dependencies and project metadata

├── copperconfig.ron # Task graph definition

└── src/

├── main.rs # Runtime entry point

├── tasks.rs # Your task implementations

└── logreader.rs # (optional) Log export utility

Which files do I actually work on?

Great news: in the next chapters, we will mainly focus on two files:

| File | What you do there | ROS 2 equivalent |

|---|---|---|

tasks.rs | Implement tasks + define message types | Node source files + .msg files |

copperconfig.ron | Define the task graph, wire connections, set parameters | Launch file + YAML params |

The rest is scaffolding that you set up once and rarely change:

| File | Role | How often you touch it |

|---|---|---|

main.rs | Boilerplate: create logger, build runtime, call run() | Rarely |

build.rs | Sets an env var for Copper’s logging macros | Never |

logreader.rs | CLI tool to decode and export Copper’s binary logs | Rarely |

Cargo.toml | Dependencies | When adding new hardware driver crates |

The mental model

Think of it this way:

copperconfig.ronis the architecture of your robot – what components exist and how they connect. It’s declarative.tasks.rsis the behavior of your robot – what each component actually does. It’s imperative Rust code.main.rsis the engine startup – it boots the runtime that executes your architecture and behavior. You don’t need to understand it deeply to get started.

In the next chapters, we’ll dive into each of these files, starting with the task graph configuration.

The Task Graph: copperconfig.ron

The file copperconfig.ron is the heart of your robot’s architecture. It defines what

tasks exist, how they connect, and what parameters they receive. Copper reads

this file at compile time to generate a deterministic scheduler.

The format is RON (Rusty Object Notation) – a human-readable data format designed for Rust.

The complete example

Here is the copperconfig.ron from our template project:

(

tasks: [

(

id: "src",

type: "tasks::MySource",

),

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

),

(

id: "sink",

type: "tasks::MySink",

),

],

cnx: [

(

src: "src",

dst: "t-0",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

(

src: "t-0",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

],

)

This defines a three-task pipeline:

MySource ──▶ MyTask ──▶ MySink

"src" "t-0" "sink"

We will discuss these 3 traits (Source, Task, Sink) later.

For the moment, let’s focus on the content of the file.

The tasks section

Each entry in the tasks array declares one task:

(

id: "src", // Unique string identifier

type: "tasks::MySource", // Rust type that implements the task

),

id– A unique name for this task instance. Used to reference it in connections.type– The fully qualified path to the Rust struct (relative to your crate root).

Optional task fields

Beyond id and type, each task entry supports several optional fields:

-

config– A key-value map of parameters passed to the task’snew()constructor as anOption<&ComponentConfig>. We’ll see how to read them in the Task Anatomy chapter.( id: "gpio", type: "cu_rp_gpio::RPGpio", config: { "pin": 4, }, ), -

missions– A list of mission IDs in which this task is active. Copper supports defining multiple “missions” (configurations of the same robot for different scenarios). A task only gets instantiated if the current mission is in its list. If omitted, the task is active in all missions.( id: "lidar", type: "tasks::LidarDriver", missions: ["outdoor", "mapping"], ), -

background– When set totrue, the task runs on a background thread instead of the critical path. Useful for tasks that do heavy or blocking work (network I/O, disk writes) that shouldn’t affect the deterministic scheduling of other tasks.( id: "telemetry", type: "tasks::TelemetryUploader", background: true, ), -

logging– Controls whether Copper’s unified logger records the output messages of this task. Setenabled: falseto reduce log size for high-frequency or uninteresting tasks.( id: "fast-sensor", type: "tasks::HighRateSensor", logging: (enabled: false), ),

The cnx (connections) section

Each entry in cnx wires one task’s output to another’s input:

(

src: "src", // Producing task's id

dst: "t-0", // Consuming task's id

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload", // Rust type of the message payload

),

-

src– Theidof the task producing the message. -

dst– Theidof the task consuming the message. -

msg– The fully qualified Rust type of the payload (see next chapter for a focus on this). -

missions(optional) – A list of mission IDs in which this connection is active, just like themissionsfield on tasks. If omitted, the connection is active in all missions.( src: "lidar", dst: "mapper", msg: "crate::tasks::PointCloud", missions: ["outdoor", "mapping"], ),

How this compares to ROS

In ROS 2, you’d create publishers and subscribers on named topics, and they’d find each

other at runtime via DDS discovery. In Copper, connections are explicit and resolved at

compile time. If you reference a task id that doesn’t exist, you get a compile error –

not a silent runtime misconfiguration.

There’s more

The configuration file we’ve seen here is minimal on purpose. Real-world Copper projects can use additional top-level sections for monitoring, logging tuning, rate limiting, missions, and modular composition. We’ll cover these throughout the book as we go.

Defining Messages

Messages (also called payloads) are the data that flows between tasks. In ROS, you’d

define these in .msg files and run a code generator. In Copper, they’re just Rust structs

with the right derives.

A custom payload

Here’s the message type from our template project (in src/tasks.rs):

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use bincode::{Decode, Encode};

use cu29::prelude::*;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Encode, Decode, Serialize, Deserialize, Reflect)]

pub struct MyPayload {

value: i32,

}

}What each derive does

Every derive on a payload struct has a specific purpose:

| Derive | Purpose |

|---|---|

Default | Required. Copper pre-allocates message buffers at startup. Default provides the initial “empty” value. |

Encode, Decode | Binary serialization for Copper’s zero-alloc message buffers and logging. These come from cu-bincode. |

Serialize, Deserialize | Used for configuration parsing, log export (MCAP, JSON), and tooling. These come from serde. |

Reflect | Runtime type introspection for monitoring tools and simulation integration. |

Debug | Human-readable printing for development. |

Clone | Allows copying messages when needed (e.g., forking data to multiple consumers). |

You do not really have to worry about all of these derives for now. Just add them each time you define a message, and we’ll see how they come into action later.

Using primitive types

For simple cases, you don’t need a custom struct at all. Primitive types like i32, f64,

and bool already implement all the required traits:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// In copperconfig.ron:

// msg: "i32"

// In your task:

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(i32);

}This is great for prototyping. As your robot grows, you’ll likely define richer message types with multiple fields.

Using units directly in payloads

Copper exposes the cu29-units wrappers (through cu29::units) so your payload fields can

carry units directly instead of raw f32 values.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use bincode::{Decode, Encode};

use cu29::prelude::*;

use cu29::units::si::f32::{Length, Time, Velocity};

use cu29::units::si::length::{inch, meter};

use cu29::units::si::time::second;

use cu29::units::si::velocity::{kilometer_per_hour, meter_per_second};

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Encode, Decode, Serialize, Deserialize, Reflect)]

pub struct WheelSample {

pub distance: Length,

pub dt: Time,

pub speed: Velocity,

}

impl WheelSample {

pub fn from_raw(distance_m: f32, dt_s: f32) -> Self {

let distance = Length::new::<meter>(distance_m);

let dt = Time::new::<second>(dt_s);

// m / s -> m/s

let speed: Velocity = (distance.into_uom() / dt.into_uom()).into(); // this is type safe

Self {

distance,

dt,

speed,

}

}

pub fn distance_in_inches(&self) -> f32 {

self.distance.get::<inch>()

}

pub fn speed_mps(&self) -> f32 {

self.speed.get::<meter_per_second>()

}

pub fn speed_kph(&self) -> f32 {

self.speed.get::<kilometer_per_hour>()

}

}

}This gives you unit-safe fields in messages, unit-safe math when building messages, and explicit

conversions when consuming them. Wrapper types support same-dimension arithmetic (+, -) and

scalar scale (* f32, / f32) directly; for cross-dimension operations (like Length / Time),

compute with the underlying uom quantity and convert back with .into() (or from_uom).

Designing good payloads

A few tips for payload design:

- Keep payloads small. They’re pre-allocated and copied between cycles. Large payloads waste memory and cache space.

- Use fixed-size types. Avoid

StringorVecon the critical path. Prefer arrays, fixed-size buffers, or enums. - One struct per “topic”. Each connection in

copperconfig.roncarries exactly one message type. If you need to send different kinds of data, define different structs and use separate connections.

Example: an IMU payload

Here’s what a more realistic payload might look like for an IMU sensor (from here):

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Encode, Decode, Serialize, Deserialize, Reflect)]

pub struct ImuPayload {

pub accel_x: Acceleration,

pub accel_y: Acceleration,

pub accel_z: Acceleration,

pub gyro_x: AngularVelocity,

pub gyro_y: AngularVelocity,

pub gyro_z: AngularVelocity,

pub temperature: ThermodynamicTemperature,

}

}In the next chapter, we’ll see how tasks produce and consume these messages.

For more advanced unit algebra, dimensions, and available units, see the underlying

uom crate docs.

Writing Tasks: tasks.rs

In the previous chapters we looked at copperconfig.ron (the architecture) and message

payloads (the data). Now let’s look at tasks.rs – where the actual behavior lives.

Just like the task graph chapter, we’ll start with the complete file and then break it down piece by piece.

The complete file

Here is the full tasks.rs from our template project:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use bincode::{Decode, Encode};

use cu29::prelude::*;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

// Define a message type

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Encode, Decode, Serialize, Deserialize, Reflect)]

pub struct MyPayload {

value: i32,

}

// Defines a source (ie. driver)

#[derive(Default, Reflect)]

pub struct MySource {}

impl Freezable for MySource {}

impl CuSrcTask for MySource {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 42 });

Ok(())

}

}

// Defines a processing task

#[derive(Reflect)]

pub struct MyTask {}

impl Freezable for MyTask {}

impl CuTask for MyTask {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(

&mut self,

_clock: &RobotClock,

input: &Self::Input<'_>,

output: &mut Self::Output<'_>,

) -> CuResult<()> {

debug!("Received message: {}", input.payload().unwrap().value);

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 43 });

Ok(())

}

}

// Defines a sink (ie. actuation)

#[derive(Default, Reflect)]

pub struct MySink {}

impl Freezable for MySink {}

impl CuSinkTask for MySink {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

debug!("Sink Received message: {}", input.payload().unwrap().value);

Ok(())

}

}

}That’s the entire file. Let’s walk through it section by section.

The imports

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

use bincode::{Decode, Encode};

use cu29::prelude::*;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

}cu29::prelude::*– Brings in everything you need from Copper: task traits,RobotClock,ComponentConfig,CuResult,Freezable,Reflect, theinput_msg!/output_msg!macros, and thedebug!logging macro.bincodeandserde– For the serialization derives onMyPayload(covered in the Defining Messages chapter).

The message type

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Encode, Decode, Serialize, Deserialize, Reflect)]

pub struct MyPayload {

value: i32,

}

}We already covered this in the previous chapter. This is the data that flows between tasks

through the connections defined in copperconfig.ron.

The three task traits

The file defines three structs, each implementing a different trait. Copper provides three task traits for the three roles a task can play in the pipeline:

| Trait | Role | Has Input? | Has Output? | ROS Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

CuSrcTask | Produces data | No | Yes | Publisher / driver node |

CuTask | Transforms data | Yes | Yes | Subscriber + Publisher |

CuSinkTask | Consumes data | Yes | No | Subscriber / actuator node |

Let’s look at each one.

Source Task: CuSrcTask – MySource

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Default, Reflect)]

pub struct MySource {}

impl Freezable for MySource {}

impl CuSrcTask for MySource {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 42 });

Ok(())

}

}

}A source is the entry point of data into the pipeline. It has no input – it generates data, typically by reading from hardware (a camera, an IMU, a GPIO pin).

What happens each cycle: The runtime calls process(), and MySource writes a

MyPayload { value: 42 } into the pre-allocated output buffer. Downstream tasks will

read this value.

Notice the process() signature: it only has output, no input.

Processing Task: CuTask – MyTask

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Reflect)]

pub struct MyTask {}

impl Freezable for MyTask {}

impl CuTask for MyTask {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(

&mut self,

_clock: &RobotClock,

input: &Self::Input<'_>,

output: &mut Self::Output<'_>,

) -> CuResult<()> {

debug!("Received message: {}", input.payload().unwrap().value);

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 43 });

Ok(())

}

}

}A processing task sits in the middle of the pipeline. It reads from upstream and writes downstream.

What happens each cycle: The runtime first runs the upstream source, then calls this

task’s process() with the source’s output as input. The task reads the value, logs it,

and writes a new value to its own output for the sink downstream.

Notice the process() signature: it has both input and output.

Sink Task: CuSinkTask – MySink

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[derive(Default, Reflect)]

pub struct MySink {}

impl Freezable for MySink {}

impl CuSinkTask for MySink {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

debug!("Sink Received message: {}", input.payload().unwrap().value);

Ok(())

}

}

}A sink is the end of the pipeline. It receives data but produces no output. Typically this drives an actuator, writes to a display, or sends data to an external system.

What happens each cycle: The runtime calls process() with the upstream task’s output.

The sink reads the value and does something with it (here, it logs it).

Notice the process() signature: it only has input, no output.

Tying it back to the task graph

Remember our copperconfig.ron:

tasks: [

( id: "src", type: "tasks::MySource" ),

( id: "t-0", type: "tasks::MyTask" ),

( id: "sink", type: "tasks::MySink" ),

],

Each type field points to one of the structs we just defined. The connections in cnx

determine which task’s output feeds into which task’s input. The Rust compiler verifies

that the message types match at build time.

In the next chapter, we’ll dissect our task to look more closely at each associated type and method in order to understand exactly what they do.

Task Anatomy: Types and Methods

Now that you’ve seen the three task traits, let’s look closely at the associated types and methods that make them work.

Associated Types

type Resources<'r> and impl Freezable

We’ll cover these in detail in the

Advanced Task Features chapter. For now, notice that both are

defined as empty – type Resources<'r> = () and impl Freezable for MyTask {} – which

is all you need for a simple project.

type Input<'m> (CuTask and CuSinkTask only)

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

}Declares what messages this task receives from upstream. The input_msg!() macro wraps

your payload type into Copper’s message container (CuMsg<T>), which carries:

- The payload itself (your struct)

- Metadata (timestamps, status flags)

- Time of Validity (

tov)

Multiple inputs: If a task receives data from multiple upstream tasks, list the types separated by commas:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(SensorA, SensorB);

}In process(), the input parameter becomes a tuple that you can destructure:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>, ...) -> CuResult<()> {

let (sensor_a_msg, sensor_b_msg) = *input;

// Use sensor_a_msg.payload() and sensor_b_msg.payload()

Ok(())

}

}type Output<'m> (CuSrcTask and CuTask only)

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

}Declares what messages this task produces for downstream. The output buffer is

pre-allocated by the runtime at startup. You don’t create messages – you fill them

using set_payload().

Methods

fn new(config, resources) -> CuResult<Self>

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn new(

_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>,

_resources: Self::Resources<'_>,

) -> CuResult<Self>

where

Self: Sized,

{

Ok(Self {})

}

}The constructor. Called once when the runtime builds the task graph.

config: Option<&ComponentConfig> is a key-value map from the task’s config block

in copperconfig.ron. For example, if your RON file has:

(

id: "motor",

type: "tasks::MotorDriver",

config: { "pin": 4, "max_speed": 1.0 },

),

You can read the values in new():

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn new(config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self> {

let cfg = config.ok_or("MotorDriver requires a config block")?;

let pin: u8 = cfg.get("pin").unwrap().clone().into();

let max_speed: f64 = cfg.get("max_speed").unwrap().clone().into();

Ok(Self { pin, max_speed })

}

}We’ll discuss resources in future chapters.

fn process() – the main loop

This is where your task does its work. The runtime calls it every cycle. The signature depends on the trait:

| Trait | Signature |

|---|---|

CuSrcTask | process(&mut self, clock, output) |

CuTask | process(&mut self, clock, input, output) |

CuSinkTask | process(&mut self, clock, input) |

In our simple example, the source ignores most parameters and just writes a value:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 42 });

Ok(())

}

}Let’s look at what each parameter gives you.

Reading input

input.payload() returns Option<&T> – an Option because the message could be empty

(e.g., the upstream task had nothing to send this cycle). In production you should handle

None; in our example we just unwrap:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let value = input.payload().unwrap();

}Writing output

output.set_payload(value) writes your data into a buffer that was pre-allocated at

startup.

The clock: &RobotClock

Every process() receives a clock parameter. This is Copper’s only clock – a

monotonic clock that starts at zero when your program launches and ticks forward in

nanoseconds. There is no UTC or wall-clock in Copper; tasks should never call

std::time::SystemTime::now() or std::time::Instant::now().

clock.now() returns a CuTime (a u64 of nanoseconds since startup). In our simple

project we prefix the parameter with _ because we don’t use it. But on a real robot

you’d use it like this:

Timestamp your output (typical for source tasks):

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: read_sensor() });

output.tov = Tov::Time(clock.now());

Ok(())

}

}Compute a time delta (e.g., for a PID controller):

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

let now = clock.now();

let dt = now - self.last_time; // CuDuration in nanoseconds

self.last_time = now;

let error = self.target - input.payload().unwrap().value;

let correction = self.kp * error + self.ki * self.integral * dt.as_secs_f64();

// ...

Ok(())

}

}Detect a timeout:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

if input.payload().is_none() {

let elapsed = clock.now() - self.last_seen;

if elapsed > CuDuration::from_millis(100) {

debug!("Sensor timeout! No data for {}ms", elapsed.as_millis());

}

}

Ok(())

}

}Why not use the system clock? Because Copper supports deterministic replay. When

you replay a recorded run, the runtime feeds your tasks the exact same clock values from

the original recording. If you used std::time, the replay would have different

timestamps and your tasks would behave differently. With RobotClock, same clock + same

inputs = same outputs, every time.

The golden rule of process()

Because process() runs on the real-time critical path (potentially thousands of

times per second), you should avoid heap allocation inside it. Operations like

Vec::push(), String::from(), or Box::new() ask the system allocator for memory,

which can take an unpredictable amount of time and cause your cycle to miss its deadline.

Copper’s architecture is designed so you never need to allocate in process(): messages

are pre-allocated, and the structured logger writes to pre-mapped memory. Keep your

process() fast and predictable.

So far we’ve focused on new() and process() – the two methods you’ll always

implement. But Copper tasks have a richer lifecycle with optional hooks for setup,

teardown, and work that doesn’t need to run on the critical path. Let’s look at that next.

Task Lifecycle

Beyond new() and process(), Copper tasks have a full lifecycle with optional hooks for

setup, teardown, and non-critical work. Understanding this lifecycle helps you put the

right code in the right place.

The full lifecycle

new() → start() → [ preprocess() → process() → postprocess() ] → stop()

└──────────── repeats every cycle ────────────┘

Lifecycle methods

| Method | When | Thread | What to do here |

|---|---|---|---|

new() | Once, at construction | Main | Read config, initialize state |

start() | Once, before the first cycle | Main | Open file handles, initialize hardware, allocate buffers |

preprocess() | Every cycle, before process() | Best-effort | Heavy prep work: decompression, FFT, parsing |

process() | Every cycle | Critical path | Core logic. Keep it fast. No allocations. |

postprocess() | Every cycle, after process() | Best-effort | Telemetry, non-critical logging, statistics |

stop() | Once, after the last cycle | Main | Cleanup: close files, stop hardware, free resources |

The two threads

Copper splits each cycle across two execution contexts:

Critical path thread

This is where process() runs. Tasks execute back-to-back in the order determined by

the task graph topology. The runtime minimizes latency and jitter on this thread. You must

avoid allocations, system calls, and anything that could block.

Best-effort thread

This is where preprocess() and postprocess() run. The runtime schedules these to

minimize interference with the critical path. You can safely do heavier work here:

I/O, allocations, logging, network calls.

What if preprocess() is late?

The critical path never waits for the best-effort thread. If preprocess() takes

longer than expected and hasn’t finished when the critical path is ready, process() runs

anyway – with whatever data is available from the previous cycle (or nothing, if it’s the

first one).

This is intentional: in a real-time system, a late result is a wrong result. It’s better

to run your control loop on slightly stale data than to miss a deadline. Your process()

should handle this gracefully:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn preprocess(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock) -> CuResult<()> {

// Heavy work on the best-effort thread -- might be slow

self.decoded_image = Some(decode_jpeg(&self.raw_buffer));

Ok(())

}

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>,

output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

// Use whatever is ready. If preprocess was late, decoded_image

// still holds the previous cycle's result (or None on first cycle).

if let Some(ref image) = self.decoded_image {

output.set_payload(run_inference(image));

}

Ok(())

}

}The same applies to postprocess(): if it falls behind, the next cycle’s process()

still runs on time.

Example: when to use each method

Imagine an IMU driver task:

new() → Read the SPI bus config from ComponentConfig

start() → Open the SPI device, configure the sensor registers

preprocess() → (not needed for this task)

process() → Read raw bytes from SPI, convert to ImuReading, set_payload()

postprocess() → Log statistics (sample rate, error count)

stop() → Close the SPI device

Or a computer vision task:

new() → Load the model weights

start() → Initialize the inference engine

preprocess() → Decode the JPEG image from the camera (heavy, OK on best-effort thread)

process() → Run inference on the decoded image, output detections

postprocess() → Update FPS counter, send telemetry

stop() → Release GPU resources

All lifecycle methods are optional

new() and process() are required – everything else has a default no-op implementation.

You only implement the lifecycle methods you need:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

impl CuTask for MyTask {

type Resources<'r> = ();

type Input<'m> = input_msg!(MyPayload);

type Output<'m> = output_msg!(MyPayload);

// Required: constructor

fn new(_config: Option<&ComponentConfig>, _resources: Self::Resources<'_>) -> CuResult<Self>

where Self: Sized {

Ok(Self {})

}

// Required: core logic

fn process(&mut self, _clock: &RobotClock, input: &Self::Input<'_>,

output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

// your core logic

Ok(())

}

// Optionally implement any of these:

// fn start(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock) -> CuResult<()> { ... }

// fn stop(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock) -> CuResult<()> { ... }

// fn preprocess(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock) -> CuResult<()> { ... }

// fn postprocess(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock) -> CuResult<()> { ... }

}

}Freeze and thaw (state snapshots)

Copper automatically logs every message flowing between tasks. But messages alone aren’t enough to reproduce a task’s behavior – you also need its internal state.

Consider a PID controller that accumulates error over time. If you want to replay from minute 7 of a 10-minute run to debug a crash, you need to know what the accumulated error was at minute 7. Without state snapshots, you’d have to replay from the very start and wait 7 minutes to get there.

That’s what freeze and thaw solve. The Freezable trait gives each task two hooks:

freeze()– Save the task’s internal state. Called periodically by the runtime to create “keyframes.”thaw()– Restore the task’s state from a saved snapshot.

These are not part of the per-cycle loop. They run at a much lower rate and are independent of the critical path:

┌─── cycle ───┐ ┌─── cycle ───┐ ┌─── cycle ───┐

... ─── process() ─── process() ─── ... ─── process() ─── ...

│ │

freeze() freeze()

(keyframe) (keyframe)

Think of it like a video codec: process() runs every frame, while freeze() saves a

keyframe at a low rate. During replay, the runtime jumps to the nearest keyframe before

minute 7, restores every task’s state via thaw(), and replays from there – no need to

start from the beginning.

For stateless tasks (like our simple MySource, MyTask, MySink), the empty

impl Freezable is fine – there’s nothing to snapshot. We’ll cover how to implement

freeze and thaw for stateful tasks in the

Advanced Task Features chapter.

The Remaining Files and Running

We’ve covered copperconfig.ron and tasks.rs – the two files you’ll edit most. Now

let’s look at the three remaining files: main.rs, build.rs, and Cargo.toml. These

are mostly boilerplate that you write once and rarely touch.

main.rs – the entry point

pub mod tasks;

use cu29::prelude::*;

use cu29_helpers::basic_copper_setup;

use std::path::{Path, PathBuf};

use std::thread::sleep;

use std::time::Duration;

const PREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE: Option<usize> = Some(1024 * 1024 * 100);

#[copper_runtime(config = "copperconfig.ron")]

struct MyProjectApplication {}

fn main() {

let logger_path = "logs/my-project.copper";

if let Some(parent) = Path::new(logger_path).parent() {

if !parent.exists() {

std::fs::create_dir_all(parent).expect("Failed to create logs directory");

}

}

let copper_ctx = basic_copper_setup(

&PathBuf::from(&logger_path),

PREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE,

true,

None,

)

.expect("Failed to setup logger.");

debug!("Logger created at {}.", logger_path);

debug!("Creating application... ");

let mut application = MyProjectApplicationBuilder::new()

.with_context(&copper_ctx)

.build()

.expect("Failed to create application.");

let clock = copper_ctx.clock.clone();

debug!("Running... starting clock: {}.", clock.now());

application.run().expect("Failed to run application.");

debug!("End of program: {}.", clock.now());

sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

}Here’s what each part does:

pub mod tasks; – Brings in your tasks.rs. The task types you defined there

(e.g., tasks::MySource) are what copperconfig.ron references.

#[copper_runtime(config = "copperconfig.ron")] – The key macro. At compile time,

it reads your config file, parses the task graph, computes a topological execution order,

and generates a custom runtime struct with a deterministic scheduler. It also creates a

builder struct named MyProjectApplicationBuilder. The struct itself is empty – all the

generated code is injected by the macro.

PREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE – How much memory (in bytes) to pre-allocate for the

structured log. 100 MB is a reasonable default.

basic_copper_setup() – Initializes the unified logger, the robot clock, and returns

a copper_ctx that holds references to both. The parameters are: log file path,

pre-allocated size, whether to also print to console, and an optional custom monitor.

MyProjectApplicationBuilder::new().with_context(&copper_ctx).build() – Wires

everything together: creates each task by calling their new() constructors,

pre-allocates all message buffers, and sets up the scheduler.

application.run() – Starts the deterministic execution loop. Calls start() on

all tasks, then enters the cycle loop (preprocess -> process -> postprocess for

each task, in topological order), and continues until you stop the application (Ctrl+C).

copper_ctx.clock.clone() – Note that we clone the clock after passing

copper_ctx to the builder, to avoid a partial-move error.

build.rs – log index setup

fn main() {

println!(

"cargo:rustc-env=LOG_INDEX_DIR={}",

std::env::var("OUT_DIR").unwrap()

);

}This sets the LOG_INDEX_DIR environment variable at compile time. Copper’s logging macros

(debug!, info!, etc.) need it to generate a string index for log messages. Without it,

you’ll get:

no LOG_INDEX_DIR system variable set, be sure build.rs sets it

You never need to change this file. Just make sure it exists.

Controlling the Loop Frequency

If you’ve run our project, you noticed that the output scrolls extremely fast. That’s because by default, Copper runs the task graph as fast as possible – there’s no rate limiter. On a modern machine, that can mean hundreds of thousands of cycles per second.

In this chapter, we’ll see how fast the loop actually runs and how to set a target frequency.

How fast is it running?

Let’s modify MySource in tasks.rs to print the time at each cycle. Replace the

process() method:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

fn process(&mut self, clock: &RobotClock, output: &mut Self::Output<'_>) -> CuResult<()> {

debug!("Source at {}µs", clock.now().as_micros());

output.set_payload(MyPayload { value: 42 });

Ok(())

}

}Run the project and look at the timestamps:

00:00:00.5296 [Debug] Source at 529632

00:00:00.5297 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:00.5298 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

00:00:00.5300 [Debug] Source at 530005

00:00:00.5301 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:00.5302 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

...

The values are in microseconds. The gap between two Source at ... lines is a few hundred

microseconds. Without a rate limiter, the loop runs as fast as it can – potentially

thousands of cycles per second, pegging a CPU core at 100%. Way too fast for most applications – and it will peg a CPU

core at 100%.

Setting a target frequency

Copper provides a simple way to rate-limit the execution loop. Add a runtime section to

your copperconfig.ron:

(

tasks: [

(

id: "src",

type: "tasks::MySource",

),

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

),

(

id: "sink",

type: "tasks::MySink",

),

],

cnx: [

(

src: "src",

dst: "t-0",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

(

src: "t-0",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

],

runtime: (

rate_target_hz: 1,

),

)

The only change is the runtime section at the bottom. rate_target_hz: 1 tells Copper

to target 1 cycle per second (1 Hz).

Run again:

00:00:00.0005 [Debug] Source at 510

00:00:00.0005 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:00.0005 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

00:00:01.0000 [Debug] Source at 1000019

00:00:01.0001 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:01.0001 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

Now each full cycle (source -> task -> sink) runs once per second.

How it works

rate_target_hz acts as a rate limiter, not a scheduler. After each complete cycle,

the runtime checks how much time has elapsed. If the cycle finished faster than the target

period (e.g., under 10ms for 100 Hz), the runtime waits for the remaining time. If the

cycle took longer than the target period, the next cycle starts immediately – no time is

wasted.

This means:

- Your actual frequency is at most

rate_target_hz. - If your tasks are too slow for the target, the loop runs at whatever rate it can sustain.

- Without the

runtimesection, the loop runs flat-out with no pause between cycles.

Difference with ROS

In ROS, each node controls its own frequency. A camera node publishes at 30 Hz, an IMU

node publishes at 200 Hz, and a planner node runs at 10 Hz – all independently. Nodes

are loosely coupled via topics, and each one has its own rospy.Rate() or rclcpp::Rate

timer that governs how often it publishes.

Copper works differently. There is one global loop that executes the entire task graph

in sequence: source -> processing -> sink, back-to-back, in topological order. Every task

runs every cycle, as fast as possible. The rate_target_hz setting doesn’t make

individual tasks run at different speeds – it tells the runtime how long to wait

between cycles so the whole pipeline doesn’t run flat-out and peg the CPU.

ROS: Node A (30 Hz) ──┐

Node B (200 Hz) ──┼── independent timers, publish on topics

Node C (10 Hz) ──┘

Copper: [ Source → Task → Sink ] → wait → [ Source → Task → Sink ] → wait → ...

└──── one cycle ────────┘ └──── one cycle ────────┘

global rate_target_hz

The key insight: in Copper, all tasks share the same cadence. If you need different parts of your system to run at different rates (e.g., a fast inner control loop and a slow planner), you’d use separate task graphs or implement logic inside a task to skip cycles. But for most applications, a single frequency for the whole pipeline is simpler and avoids the synchronization headaches that come with multiple independent timers.

Adding the Console Monitor

In the previous chapter we controlled the loop frequency. But how do we know how fast each

task actually runs? How much time does process() take? What’s the jitter?

Copper comes with a built-in TUI (terminal user interface) monitor called CuConsoleMon that displays live statistics for every task in your pipeline – mean execution time, standard deviation, min, max, and more.

Step 1: Add the dependency

Add cu-consolemon to your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

cu29 = { git = "https://github.com/copper-project/copper-rs" }

cu29-helpers = { git = "https://github.com/copper-project/copper-rs" }

cu-consolemon = { git = "https://github.com/copper-project/copper-rs" }

bincode = { package = "cu-bincode", version = "2.0", default-features = false,

features = ["derive", "alloc"] }

serde = { version = "1", features = ["derive"] }

The only new line is cu-consolemon.

Step 2: Enable it in copperconfig.ron

Add a monitor section to your copperconfig.ron:

(

tasks: [

(

id: "src",

type: "tasks::MySource",

),

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

),

(

id: "sink",

type: "tasks::MySink",

),

],

cnx: [

(

src: "src",

dst: "t-0",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

(

src: "t-0",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

],

runtime: (

rate_target_hz: 1,

),

monitor: (

type: "cu_consolemon::CuConsoleMon",

),

)

Step 3: Run

cargo run

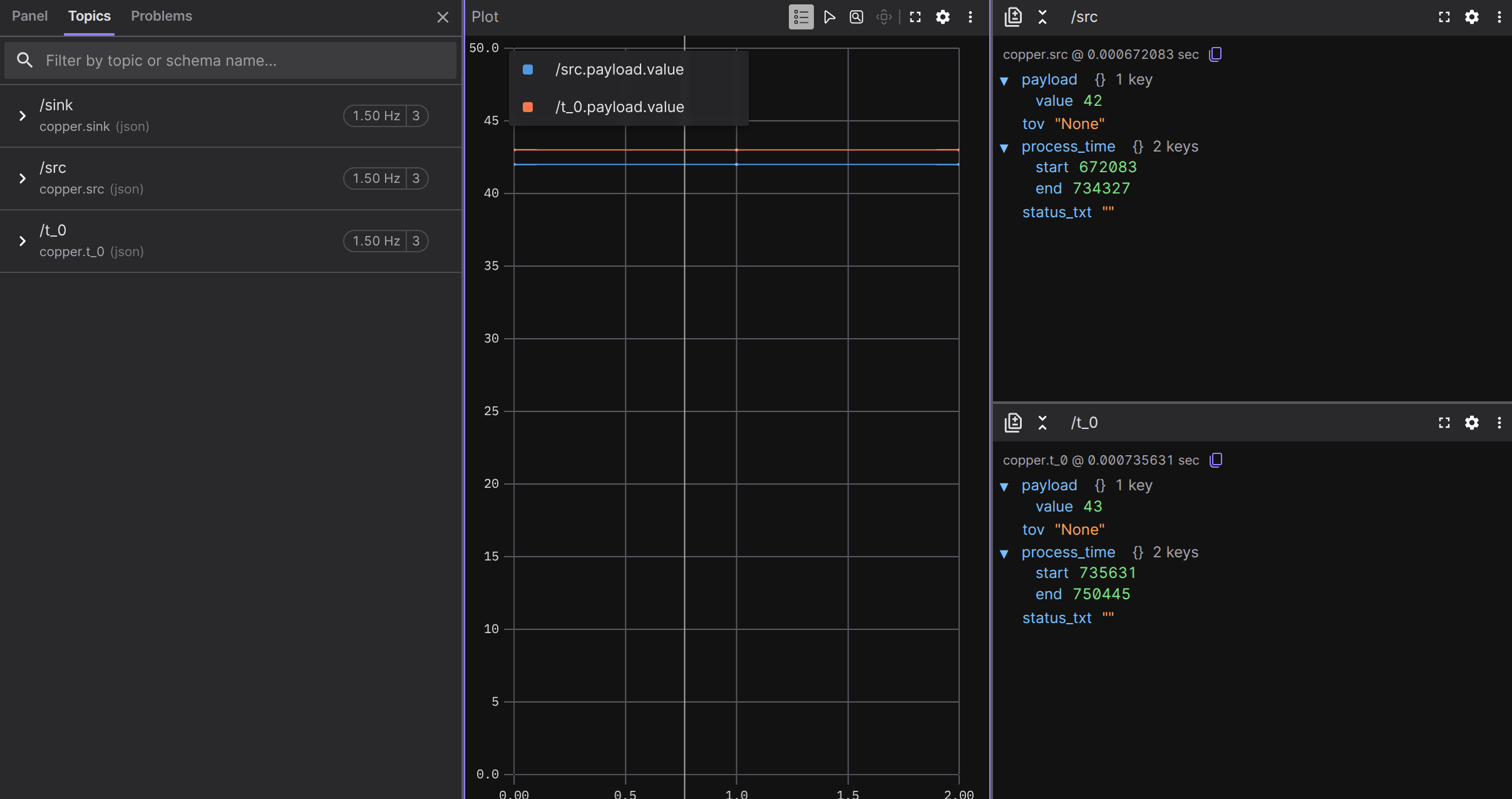

Instead of the scrolling debug output you’re used to, you’ll see a live terminal dashboard that takes over your terminal. Navigate to the latency tab (you can click on it)

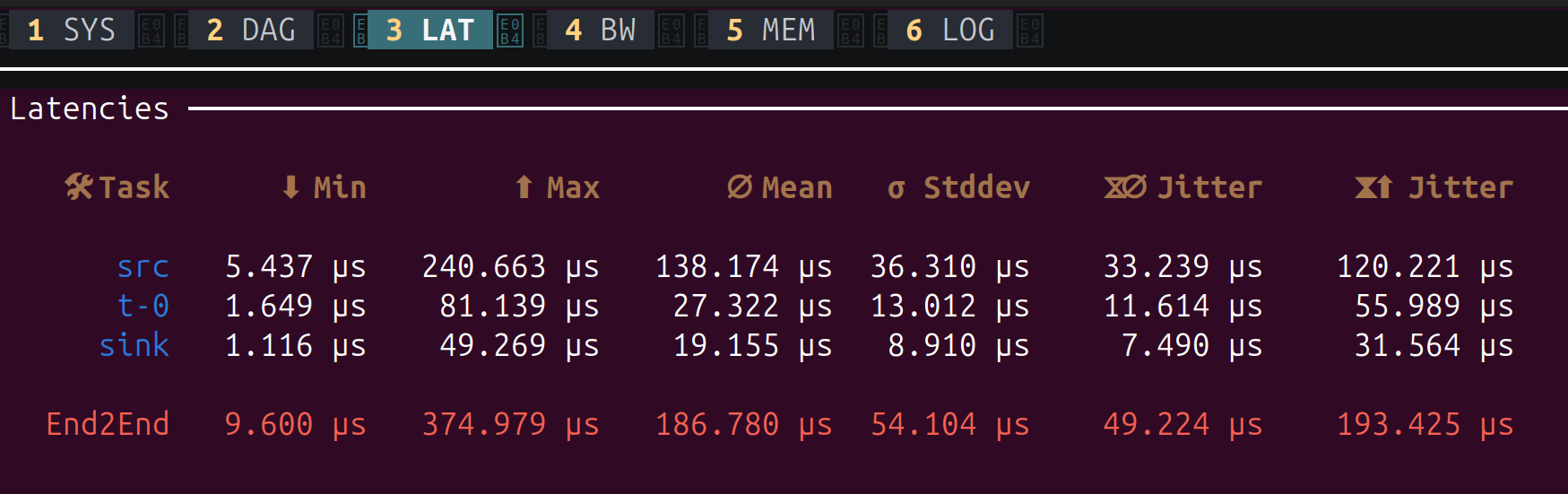

The latency tab shows one row per task, plus an End2End row at the bottom for the entire pipeline. Here’s what each column means:

| Column | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Task | The task id from your copperconfig.ron |

| Min | Fastest process() execution seen across all cycles |

| Max | Slowest process() execution seen (watch for spikes here) |

| Mean | Average process() execution time |

| Stddev | Standard deviation – how much the execution time varies. Lower is more predictable |

| Jitter (mean) | Average difference between consecutive cycle times. Indicates how stable the timing is |

| Jitter (max) | Worst-case jitter seen. A large value means occasional timing spikes |

The End2End row measures the full pipeline latency: from the start of src to the end

of sink. In our example, the entire pipeline completes in about 187 µs on average, with

a worst case of 375 µs.

This is extremely useful for:

- Verifying your frequency: Are your tasks fast enough for the target

rate_target_hz? - Finding bottlenecks: Which task takes the most time?

- Detecting jitter: A high Std Dev means unpredictable execution time, which could be a problem for real-time control.

Difference with ROS

In ROS 2, getting this kind of per-node timing data typically requires external tools like

ros2 topic hz, ros2 topic delay, or hooking up a tracing framework. Each tool gives

you one metric at a time, for one topic.

In Copper, the console monitor is built into the runtime. One line of config gives you a live dashboard of every task in the system, with no external tooling needed.

Press Ctrl+C to stop the application as usual.

The other tabs

The monitor has six tabs, accessible by pressing 1 through 6 or clicking on them.

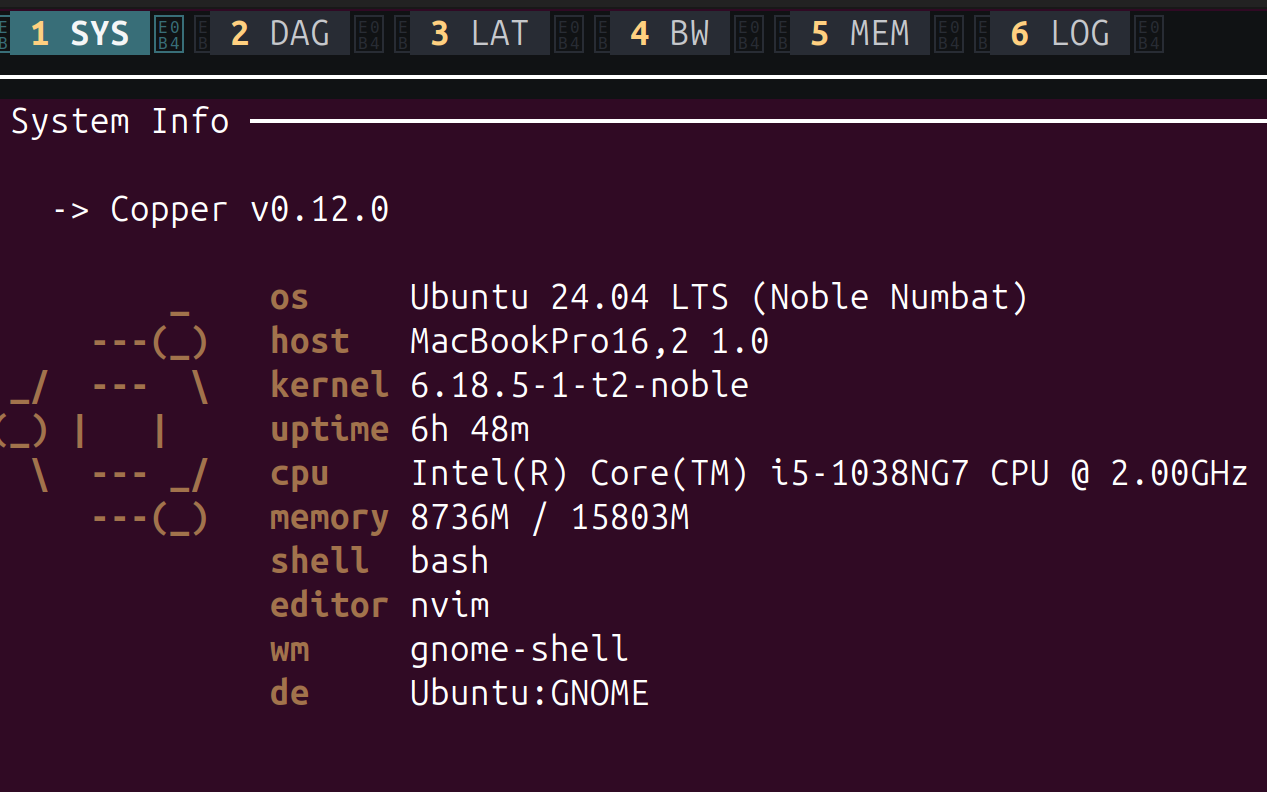

1 - SYS: System Info

Displays your system information: OS, kernel, CPU, memory, and the Copper version. Useful for documenting what hardware a recording was made on.

2 - DAG: Task Graph

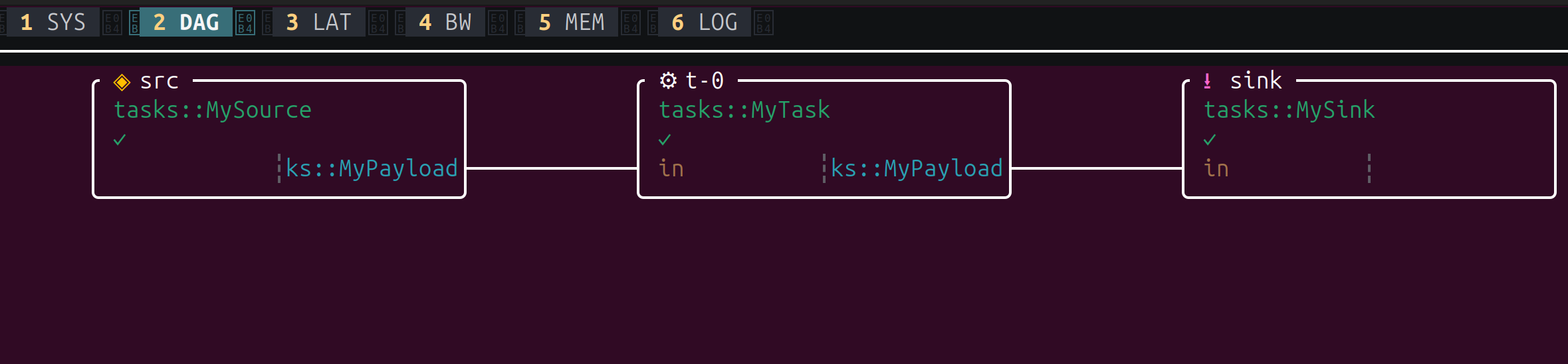

A visual representation of your task graph. Each box is a task, showing its id, Rust

type, and the message types on its connections. This is your copperconfig.ron rendered

live – a quick way to verify the pipeline is wired correctly.

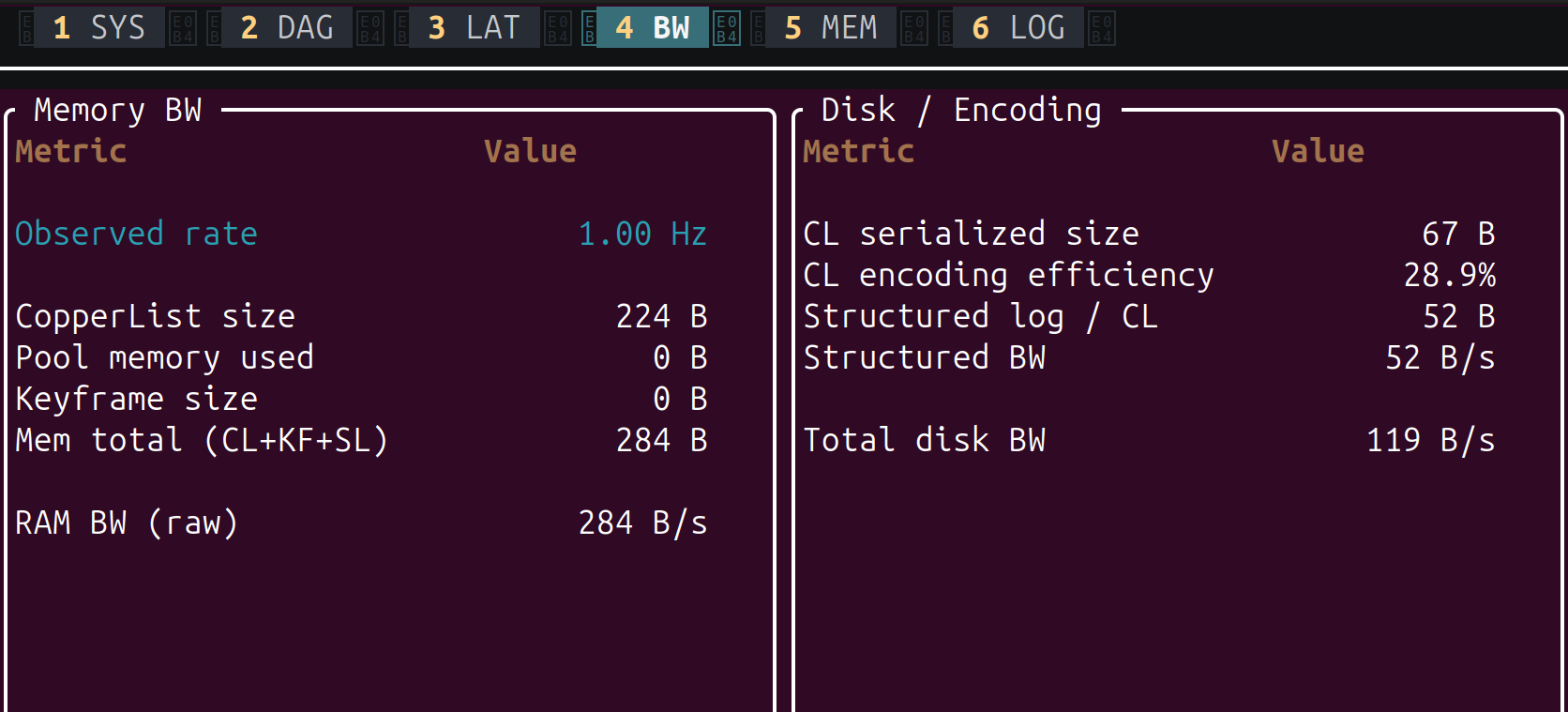

4 - BW: Bandwidth

Shows memory and disk bandwidth consumed by the runtime. The left panel (Memory BW) reports the observed loop rate, CopperList size, and raw memory throughput. The right panel (Disk / Encoding) shows the serialized size of each CopperList, encoding efficiency, structured log bandwidth, and total disk write rate. Useful for sizing your log storage and checking that the logger can keep up.

5 - MEM: Memory Pools

Displays the status of Copper’s pre-allocated memory pools: pool ID, used vs total buffers, buffer size, handles in use, and allocation rate. In our simple project the pools are empty, but on a real robot with large messages (images, point clouds), this helps you verify that buffers are correctly sized and not exhausted.

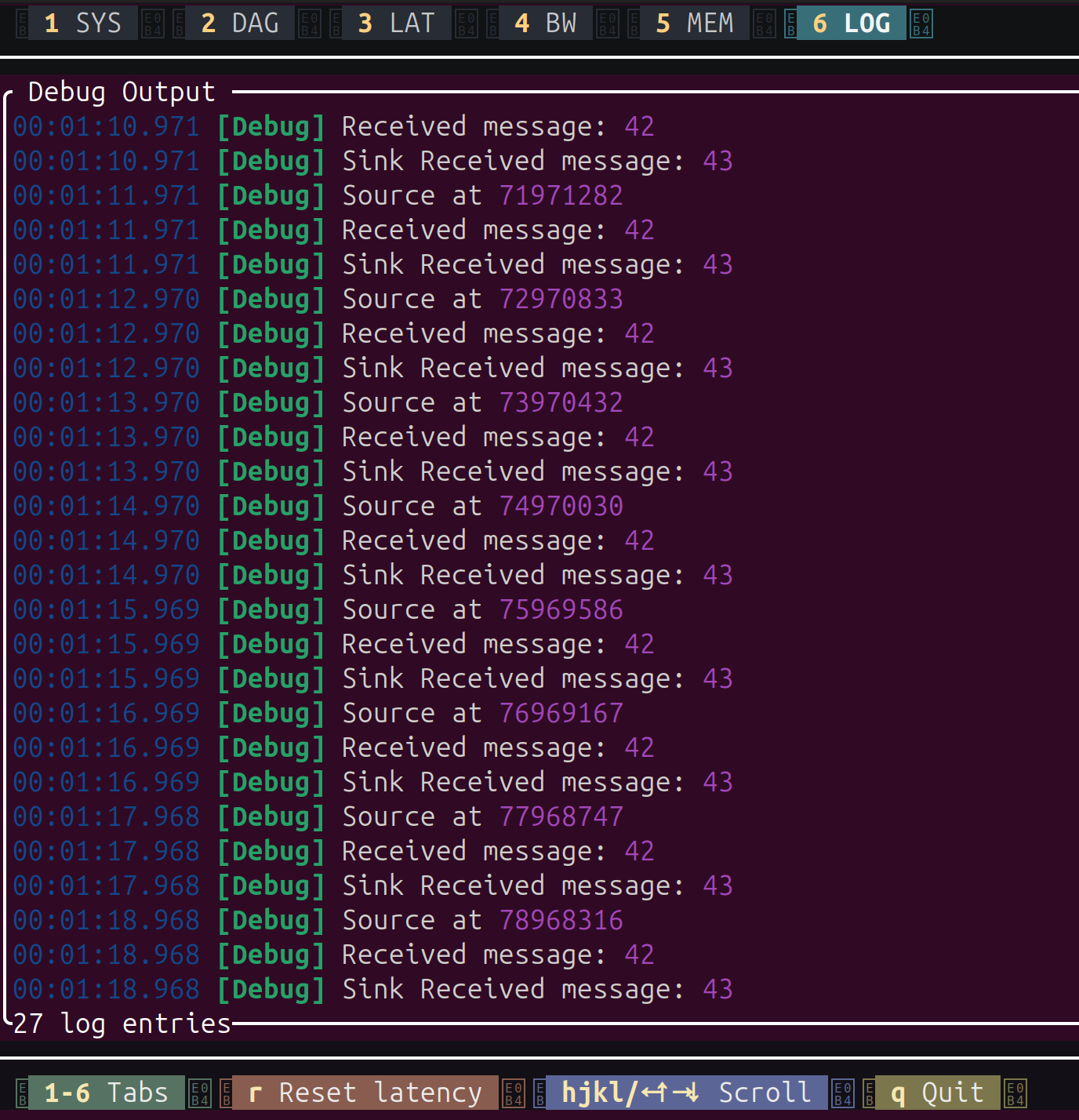

6 - LOG: Debug Output

A scrollable view of all debug!() log output from your tasks – the same messages you’d

see without the monitor, but captured inside the TUI. You can scroll through the history

with hjkl or arrow keys. The bottom bar also shows keyboard shortcuts: r to reset

latency statistics, q to quit.

Logging and Replaying Data

Every time you’ve run our project so far, Copper has been quietly recording everything.

Look at main.rs – the call to basic_copper_setup() initializes a unified logger

that writes to logs/my-project.copper. Every cycle, the runtime serializes every message

exchanged between tasks (the CopperList) and writes it to that file.

In this chapter, we’ll explore what’s in that log file, how to read it back, and how to replay recorded data through the pipeline.

What gets logged?

Copper’s unified logger captures two kinds of data in a single .copper file:

-

Structured text logs – Every

debug!(),info!(),warn!(), anderror!()call from your tasks. These are stored in an efficient binary format (not as text strings), so they’re extremely fast to write and compact on disk. -

CopperList data – The complete set of message payloads exchanged between tasks in each cycle. In our project, that means every

MyPayload { value: 42 }fromMySourceand everyMyPayload { value: 43 }fromMyTask, along with precise timestamps.

This is different from most robotics frameworks where logging is opt-in and you have to explicitly record topics. In Copper, every message is logged by default. The runtime does this automatically as part of its execution loop – no extra code needed.

Step 1: Generate a log file

Make sure your project is in the state from the previous chapters, with the 1 Hz rate

limiter. Here’s the copperconfig.ron for reference:

(

tasks: [

(

id: "src",

type: "tasks::MySource",

),

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

),

(

id: "sink",

type: "tasks::MySink",

),

],

cnx: [

(

src: "src",

dst: "t-0",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

(

src: "t-0",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

),

],

runtime: (

rate_target_hz: 1,

),

)

Note: If you still have the

monitorsection from the previous chapter, remove it for now. The console monitor takes over the terminal and makes it harder to see the debug output.

Run the project and let it execute for 5-10 seconds, then press Ctrl+C:

cargo run

00:00:03.9986 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:03.9987 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

00:00:04.9979 [Debug] Source at 4997916

00:00:04.9980 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:04.9981 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

...

After stopping, check the logs/ directory:

ls -lh logs/

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 4.0K logs/my-project.copper

That .copper file contains everything: every message, every timestamp, every debug line.

Note: The log path is hardcoded to

"logs/my-project.copper"inmain.rs. Each run overwrites the previous log file – there is no automatic rotation or timestamping. If you want to keep a log from a previous session, rename or move the file before running the project again.

Step 2: The log reader

If you look at your project, you’ll notice there’s already a file you haven’t used yet:

src/logreader.rs. The project template ships with a built-in log reader. Let’s look at

it:

pub mod tasks;

use cu29::prelude::*;

use cu29_export::run_cli;

// This will create the CuStampedDataSet that is specific to your copper project.

// It is used to instruct the log reader how to decode the logs.

gen_cumsgs!("copperconfig.ron");

#[cfg(feature = "logreader")]

fn main() {

run_cli::<CuStampedDataSet>().expect("Failed to run the export CLI");

}This is a small but powerful program. Let’s break it down:

gen_cumsgs!("copperconfig.ron") – This macro reads your task graph and generates a

CuStampedDataSet type that knows the exact message types used in your pipeline. The log

reader needs this to decode the binary data in the .copper file – without it, the bytes

would be meaningless.

run_cli::<CuStampedDataSet>() – This is Copper’s built-in export CLI. It provides

several subcommands for extracting data from .copper files. By passing the generated

CuStampedDataSet type, you tell it exactly how to decode your project’s messages.

#[cfg(feature = "logreader")] – The log reader is gated behind a Cargo feature flag

so its dependencies (like cu29-export) are only compiled when you actually need them.

Step 3: Extract text logs

The first thing you can do with the log reader is extract the structured text logs – the

debug!() messages from your tasks. Remember, these aren’t stored as text in the

.copper file; they’re stored as compact binary indices. The log reader reconstructs the

human-readable text using the string index that was built at compile time.

Run:

cargo run --features logreader --bin my-project-logreader -- \

logs/my-project.copper extract-text-log target/debug/cu29_log_index

The arguments are:

logs/my-project.copper– The log file to readextract-text-log– The subcommand to extract text logstarget/debug/cu29_log_index– The path to the string index directory (generated during compilation bybuild.rs)

You’ll see output like:

25.501 µs [Debug]: Logger created at logs/my-project.copper.

45.903 µs [Debug]: Creating application...

64.282 µs [Debug]: CuConfig: Reading configuration from file: copperconfig.ron

669.067 µs [Debug]: Running... starting clock: 666.866 µs.

823.766 µs [Debug]: Source at 822

870.122 µs [Debug]: Received message: 42

887.054 µs [Debug]: Sink Received message: 43

1.000 s [Debug]: Source at 1000206

1.000 s [Debug]: Received message: 42

1.000 s [Debug]: Sink Received message: 43

2.000 s [Debug]: Source at 1999631

...

This is the same output you saw scrolling by when the application was running – but reconstructed from the binary log after the fact.

Step 4: Extract CopperLists

The more interesting subcommand extracts the CopperList data – the actual message payloads from every cycle:

cargo run --features logreader --bin my-project-logreader -- \

logs/my-project.copper extract-copperlists

The output is JSON by default. Here’s what the first CopperList looks like:

{

"id": 0,

"state": "BeingSerialized",

"msgs": [

{

"payload": {

"value": 42

},

"tov": "None",

"metadata": {

"process_time": {

"start": 822050,

"end": 867803

},

"status_txt": ""

}

},

{

"payload": {

"value": 43

},

"tov": "None",

"metadata": {

"process_time": {

"start": 869282,

"end": 885259

},

"status_txt": ""

}

}

]

}

Every message from every cycle is there, exactly as it was produced. Each entry in msgs

corresponds to a connection in your task graph (in order: src→t-0, then t-0→sink).

Along with the payload, you get:

metadata.process_time– The start and end timestamps (in nanoseconds) of the task’sprocess()call that produced this message. This is the same timing data the console monitor uses for its latency statistics.tov– “Time of validity”, an optional timestamp that the task can set to indicate when the data was actually captured (useful for hardware drivers with their own clocks).status_txt– An optional status string the task can set for diagnostics.

This is the raw data you’d use for offline analysis, regression testing, or replay.

Why this matters: replay

Recording data is useful for post-mortem analysis, but the real power of Copper’s logging is deterministic replay. Because every message and its timestamp is recorded, you can feed logged data back into the pipeline and reproduce the exact same execution – without any hardware.

This means you can:

- Debug without hardware: Record a session on the real robot, then replay it on your laptop to test processing logic.

- Regression test: Record a known-good session, then replay it after code changes to verify the pipeline still produces the same results.

- Analyze edge cases: When your robot encounters an unusual situation, the log captures it. You can replay that exact moment over and over while you debug.

The key insight is that all downstream tasks don’t know the difference – they receive

the same MyPayload messages with the same timestamps, whether they come from live

hardware or a log file.

How the unified logger works under the hood

Copper’s logger is designed for zero-impact logging on the critical path. Here’s how:

-

Pre-allocated memory slabs – At startup,

basic_copper_setup()allocates a large contiguous block of memory (controlled byPREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE– 100 MB in our project). CopperLists are written into this pre-allocated buffer without any dynamic allocation. -

Binary serialization – Messages are serialized using

bincode, not formatted as text. This is why your payloads need theEncode/Decodederives. Binary serialization is orders of magnitude faster thanformat!()orserde_json. -

Memory-mapped I/O – The pre-allocated slabs are memory-mapped to the

.copperfile. The OS handles flushing to disk asynchronously, so the robot’s critical path never blocks on disk I/O. -

Structured text logging – Even

debug!()calls don’t format strings at runtime. Instead, Copper stores a compact index and the raw values. The actual string formatting happens only when you read the log – not when you write it. This is why thebuild.rssets upLOG_INDEX_DIR– it’s building a string table at compile time.

This means logging in Copper is almost free on the hot path. You can log everything without worrying about performance – which is exactly why it logs everything by default.

Controlling what gets logged

Sometimes you don’t want to log everything. A high-frequency sensor producing megabytes per second can fill up your log storage quickly. Copper provides two ways to control this:

Per-task logging control

In copperconfig.ron, you can disable logging for specific tasks:

(

id: "fast-sensor",

type: "tasks::HighRateSensor",

logging: (enabled: false),

),

This stops the runtime from recording that task’s output messages in the CopperList log. The task still runs normally – it just doesn’t contribute to the log file.

Global logging settings

The logging section in copperconfig.ron lets you tune the logger globally:

logging: (

slab_size_mib: 1024,

section_size_mib: 100,

),

Difference with ROS

In ROS, data recording is a separate tool: rosbag2. You start a ros2 bag record

process alongside your running nodes, tell it which topics to subscribe to, and it saves

messages into a SQLite database or MCAP file. Replay is done with ros2 bag play, which

republishes the messages on the same topics.

ROS:

Run: ros2 launch my_robot.launch.py

Record: ros2 bag record /camera /imu /cmd_vel ← separate process

Replay: ros2 bag play my_bag/ ← republishes on topics

Copper:

Run: cargo run ← logging is automatic

Read: cargo run --features logreader --bin my-project-logreader ...

Replay: feed CopperLists back into the pipeline ← deterministic

Key differences:

| ROS 2 (rosbag2) | Copper (unified logger) | |

|---|---|---|

| Opt-in vs automatic | You must explicitly record topics | Everything is logged by default |

| Separate process | ros2 bag record runs alongside | Built into the runtime – zero config |

| Format | SQLite / MCAP | Custom binary .copper format |

| Performance impact | Adds subscriber overhead per topic | Near-zero – pre-allocated, memory-mapped |

| Replay mechanism | Republishes on topics | Feed CopperLists directly into tasks |

| Deterministic | Timing depends on DDS, not guaranteed | Timestamps are recorded, replay is deterministic |

| Text logging | Separate (rosout, spdlog) | Unified – text and data in one file |

The biggest philosophical difference: in ROS, recording is something you do. In Copper,

recording is something that happens. You don’t configure it, you don’t start it, you

don’t choose which topics to record. The runtime records everything, always. You only need

to decide what to exclude (via logging: (enabled: false)) if storage is a concern.

This “record everything by default” approach is what makes Copper’s deterministic replay possible. Since every message and every timestamp is captured automatically, you can always go back and reproduce any moment of your robot’s execution.

Missions

So far, our project has a single pipeline: MySource → MyTask → MySink. Every time we

run it, the same three tasks execute in the same order. But real-world robots often need

to operate in different modes – a drone might have a “takeoff” mode and a “cruise”

mode, a warehouse robot might switch between “navigate” and “charge”, or you might want

a “simulation” mode that uses mock drivers instead of real hardware.

In many frameworks, you’d handle this with if statements scattered across your code, or

by maintaining separate launch files. Copper takes a different approach: missions.

What are missions?

A mission is a named variant of your task graph. You declare all possible tasks and

connections in a single copperconfig.ron, then tag each one with the missions it belongs

to. At build time, Copper generates a separate application builder for each mission. At

runtime, you choose which builder to use.

The key properties:

- Tasks without a

missionsfield are shared – they exist in every mission. - Tasks with a

missionsfield are selective – they only exist in the listed missions. - Connections follow the same rule – tag them with

missionsto make them mission-specific. - No recompilation needed to switch – all missions are compiled at once. You pick which one to run.

Step 1: Define missions in copperconfig.ron

Let’s modify our project to support two missions:

- “normal” – The full pipeline we’ve been using: source → processing → sink.

- “direct” – A shortcut that skips the processing task: source → sink.

This is a simple but realistic scenario. Imagine MyTask does some expensive computation

(image processing, path planning). During testing or in a degraded mode, you might want to

bypass it and send raw data straight to the sink.

Replace your copperconfig.ron with:

(

missions: [(id: "normal"), (id: "direct")],

tasks: [

(

id: "src",

type: "tasks::MySource",

),

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

missions: ["normal"],

),

(

id: "sink",

type: "tasks::MySink",

),

],

cnx: [

(

src: "src",

dst: "t-0",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

missions: ["normal"],

),

(

src: "t-0",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

missions: ["normal"],

),

(

src: "src",

dst: "sink",

msg: "crate::tasks::MyPayload",

missions: ["direct"],

),

],

runtime: (

rate_target_hz: 1,

),

)

Let’s break down what changed:

The missions declaration

missions: [(id: "normal"), (id: "direct")],

This top-level array declares all available missions. Each mission is just an ID – a string that you’ll reference elsewhere.

Shared tasks

src and sink have no missions field. This means they participate in every

mission. They are the common backbone of the pipeline.

Mission-specific tasks

(

id: "t-0",

type: "tasks::MyTask",

missions: ["normal"],

),

MyTask is tagged with missions: ["normal"]. It only exists in the “normal” mission.

When running the “direct” mission, this task is simply not instantiated.

Mission-specific connections

The connections are where the graph really diverges:

Mission "normal": src ──▶ t-0 ──▶ sink

Mission "direct": src ──────────▶ sink

In “normal”, data flows through the processing task. In “direct”, the source connects

directly to the sink, bypassing MyTask entirely.

Notice that the connection src → sink in the “direct” mission uses the same message type

(crate::tasks::MyPayload) as the other connections. This works because MySink already

accepts MyPayload as input – the message types must be compatible regardless of which

path the data takes.

Step 2: Update main.rs

When you declare missions, the #[copper_runtime] macro no longer generates a single

builder. Instead, it creates a module for each mission, named after the mission ID.

Each module contains its own builder type.

For our project, the macro generates:

normal::MyProjectApplicationBuilder– builds the “normal” pipelinedirect::MyProjectApplicationBuilder– builds the “direct” pipeline

Update main.rs to select a mission:

pub mod tasks;

use cu29::prelude::*;

use cu29_helpers::basic_copper_setup;

use std::path::{Path, PathBuf};

use std::thread::sleep;

use std::time::Duration;

const PREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE: Option<usize> = Some(1024 * 1024 * 100);

#[copper_runtime(config = "copperconfig.ron")]

struct MyProjectApplication {}

// Import the per-mission builders

use normal::MyProjectApplicationBuilder as NormalBuilder;

use direct::MyProjectApplicationBuilder as DirectBuilder;

fn main() {

// Pick the mission from the first command-line argument (default: "normal")

let mission = std::env::args()

.nth(1)

.unwrap_or_else(|| "normal".to_string());

let logger_path = "logs/my-project.copper";

if let Some(parent) = Path::new(logger_path).parent() {

if !parent.exists() {

std::fs::create_dir_all(parent).expect("Failed to create logs directory");

}

}

let copper_ctx = basic_copper_setup(

&PathBuf::from(&logger_path),

PREALLOCATED_STORAGE_SIZE,

true,

None,

)

.expect("Failed to setup logger.");

debug!("Logger created at {}.", logger_path);

match mission.as_str() {

"normal" => {

debug!("Starting mission: normal");

let mut app = NormalBuilder::new()

.with_context(&copper_ctx)

.build()

.expect("Failed to create application.");

app.run().expect("Failed to run application.");

}

"direct" => {

debug!("Starting mission: direct");

let mut app = DirectBuilder::new()

.with_context(&copper_ctx)

.build()

.expect("Failed to create application.");

app.run().expect("Failed to run application.");

}

other => {

eprintln!("Unknown mission: '{}'. Available: normal, direct", other);

std::process::exit(1);

}

}

debug!("End of program.");

sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

}The important changes:

- Two

usestatements import the builders from the generated mission modules. - A

matchon the mission name selects which builder to use. Here we read it from the command line, but you could also use an environment variable, a config file, or any other mechanism. - Each branch is independent – the “normal” branch builds a three-task pipeline, the “direct” branch builds a two-task pipeline.

No changes to tasks.rs are needed. The task implementations are the same – missions

only control which tasks are instantiated and wired, not how they behave.

Step 3: Run it

Run the “normal” mission (the default):

cargo run

00:00:00.0006 [Debug] Source at 630

00:00:00.0006 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:00.0006 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

00:00:01.0002 [Debug] Source at 1000259

00:00:01.0004 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:01.0004 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

00:00:01.9999 [Debug] Source at 1999931

00:00:02.0000 [Debug] Received message: 42

00:00:02.0001 [Debug] Sink Received message: 43

This is the full pipeline. The source produces 42, MyTask transforms it to 43, and the

sink receives 43.

Now run the “direct” mission:

cargo run -- direct

00:00:00.0005 [Debug] Source at 549

00:00:00.0005 [Debug] Sink Received message: 42

00:00:00.9999 [Debug] Source at 999945

00:00:01.0000 [Debug] Sink Received message: 42

00:00:01.9992 [Debug] Source at 1999286

00:00:01.9994 [Debug] Sink Received message: 42

00:00:02.9987 [Debug] Source at 2998704

00:00:02.9988 [Debug] Sink Received message: 42

Notice the difference: there is no “Received message: 42” line from MyTask, and the sink

receives 42 (the raw value from the source) instead of 43. MyTask was never

instantiated – the data went straight from source to sink.

Same binary, same tasks, different wiring. No recompilation.

How it works under the hood

When the #[copper_runtime] macro processes a configuration with missions, it:

- Parses all missions from the top-level

missionsarray. - For each mission, filters the task list and connection list to include only:

- Tasks/connections with no

missionsfield (shared across all missions) - Tasks/connections whose

missionsarray contains this mission’s ID

- Tasks/connections with no

- Generates a Rust module for each mission (named after the mission ID), containing a builder type, the filtered task graph, and the scheduling code.

All of this happens at compile time. The final binary contains the code for every mission, but only the tasks belonging to the selected mission are instantiated at runtime.

A task can belong to multiple missions

A task isn’t limited to a single mission. If you have a task that’s needed in several (but not all) missions, list them:

(

id: "safety-monitor",

type: "tasks::SafetyMonitor",

missions: ["navigate", "charge", "manual"],

),

This task is active in three missions but excluded from others (say, “simulation” or “diagnostics”).

When to use missions

Missions are most useful when you have:

- Hardware vs simulation: Use real drivers in one mission, mock drivers in another.

- Operating modes: Different task graphs for different phases of operation (startup, cruise, landing).

- Platform variants: The same codebase running on different hardware – one mission for the prototype with basic sensors, another for the production model with full sensor suite.

- Debug vs production: A mission with extra logging/monitoring tasks for development, and a lean mission for deployment.

Difference with ROS

In ROS 2, switching between configurations typically means maintaining separate launch files or using launch arguments with conditionals:

# ROS 2: launch file with conditionals

use_sim = LaunchConfiguration('use_sim')

Node(

package='my_robot',

executable='lidar_driver',

condition=UnlessCondition(use_sim),

),

Node(

package='my_robot',

executable='fake_lidar',

condition=IfCondition(use_sim),

),

ros2 launch my_robot robot.launch.py use_sim:=true

This works, but the logic lives in Python launch files that are completely separate from your node code. Errors (wrong topic names, missing remappings) only show up at runtime.

In Copper, everything is in one copperconfig.ron:

Copper:

copperconfig.ron ← all missions, tasks, and connections in one place

cargo run ← default mission

cargo run -- direct ← alternative mission

Key differences:

| ROS 2 | Copper | |

|---|---|---|

| Where | Python launch files + YAML params | Single copperconfig.ron |

| Validation | Runtime (nodes may fail to connect) | Compile time (macro checks the graph) |

| Granularity | Per-node conditionals | Per-task and per-connection tagging |

| Switching | Launch arguments | Builder selection in main.rs |

| All variants visible | Spread across files and conditionals | One file, all missions side by side |